Interpreting Classical Music Notation – Malcolm Bilson Interview | Op. 6

Do you really know how to read classical music from the era of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven? In this episode of Classical Cake, guest Malcolm Bilson – an expert in historical performance practices – will make you question what you’ve learned as he gives tips on interpreting musical notation.

In this episode, you’ll:

Encounter surprising contradictions between historical and modern practices

Learn new concepts about interpreting classical-era music

Understand the importance of experimentation

Get resources to learn more about historical performance practice

For the best experience, please watch the video at the top of the page.

Episode Transcript and Timestamps

DANIEL ADAM MALTZ: Grüß Sie and welcome to Classical Cake, the podcast where we discuss topics relating to Vienna’s classical music while enjoying one of Vienna's delicious cakes. I'm your host Daniel Adam Maltz.

Today's musicians use a common language to read and interpret music from all musical eras, but do we lose something with this general approach? Just as spoken language evolves over time, so does the way composers communicate their intentions. Do we as musicians, really know how to interpret the language of classical era composers such as Mozart and Beethoven?

Today we will discuss this topic with Malcolm Bilson, a pioneer in the historically-informed performance movement. Bilson is one of the most respected leaders in this field and is the Frederick J. Whiton Professor of Music Emeritus at Cornell University. He's released numerous videos including: Knowing the Score, Knowing the Score Vol. 2, Performing the Score and, most recently, Taste.

Featured Cake: Tres Leches [1:20]

We're at the Piano Technicians Guild Convention in Tucson, Arizona, far away from the cafe houses of Vienna. So our cake today will be a local specialty, Tres Leches Cake.

This tasty dessert is made by poking holes in a very light sponge cake, then soaking it in three different types of milk: evaporated milk, sweetened condensed milk and whole milk. It is then topped with sweetened whipped cream. This cake sounds like a dream for a dairy lover like me.

Let's dig in.

I hope you like sugar.

MALCOLM BILSON: I like sugar.

MALTZ: There’s a lot of it in there.

BILSON: This is terrific.

What is an ‘interpreter? [1:49]

MALTZ: Your videos show that historically informed performance provides opportunities to rediscover a musical language and to make interpretations and performances more interesting for both the audience and the performer.

At the start of Knowing the Score you discussed the word “interpreter.” Why is understanding the nuance of the word interpreter important for our approach and performing music?

BILSON: Well you see interpreter… how should I say this? I don't speak Turkish, so I need an interpreter. So the interpreter has to do two things. One, he has to understand what's being said. The second thing he has to render this as best he can. Those are two different things and it seems to me the same thing is true with music.

Now, the difficulty that somebody like me has… when you watch a film that was made in 1960 and it's about the 20s, the music that they play, will probably be not exactly like what it was in the 20s, you see. And, and we think that it should be like it was in the 20s and it shouldn't be sort of souped up to something more contemporary in 1960.

So, basically, my problem when I go and give a masterclass, I'm almost never telling anybody what to do. I'm always telling them what to read.

In other words if we take, for instance, Mozart. Mozart writes two things in his scores, one of them is the notes. These are these little round guys that are either in a space or on a line and if you know what they are, then this is considered reading music.

But, Mozart writes something else and that is he writes what we call articulations slurs, half-moon, crescents over notes, dots over notes, accents over notes, piano, forte, and all of these things tell us the meaning of the music.

And I simply believe that if you change these as most modern players do into this sort of long – my friend Robert Levin calls it ‘maple syrup over everything’ – that you're losing the drama. And that's not really Mozart's music. I mean, it's as simple as that.

Note Lengths [4:36]

MALTZ: Well, you opened my eyes to a completely different, freeing way of interpreting music. So, for the next few questions, I want to highlight some of the concepts that I think will be most interesting to those interpreting music of the classical era.

The first concept is note lengths. For example, how long do we hold down a quarter note or an eighth note or a 16th note?

BILSON: Yes. There's an old joke. The pianist, Harold Bauer, was a very famous English pianist about a hundred years ago. A woman came to him and she said, ‘I'm thinking of a note,’

And Harold Bauer said, ‘A quarter-note?’

‘No, shorter than that.’

‘An eighth-note?’

‘No, no, shorter than that.’

‘A 16th-note?’

‘Yes, a 16th-note. Play me one.’

Now, of course, you cannot play one 16th note because it's only how long it takes to get to the next one that has any sense. But basically, I think what is very shocking and difficult for a lot of young players is the whole idea that you play everything legato is something that really happens in the early 19th century.

And the idea is that notes that are not marked in any way – especially with one of these slurs, these crescent-shaped curved things – so that any note that is not marked that way is not to be held full length.

And that's shocking enough in itself. But the greater problem is, well, how long should it be? They talked about this in the 18th century, it’s really not so complicated. They talk about heavy music and light music and the lighter the music, the shorter the notes. If it's not connected, but heavy… it's not just that it's slower, but that the proportion of the time that it takes is greater. And, this is how we understand comedy from a tragedy, basically.

What else should we read from slurs? [6:43]

MALTZ: So you've already talked about slurs a little bit, and you say in your videos that slurs mean more than just simply play legato. So what else should we be reading from slurs?

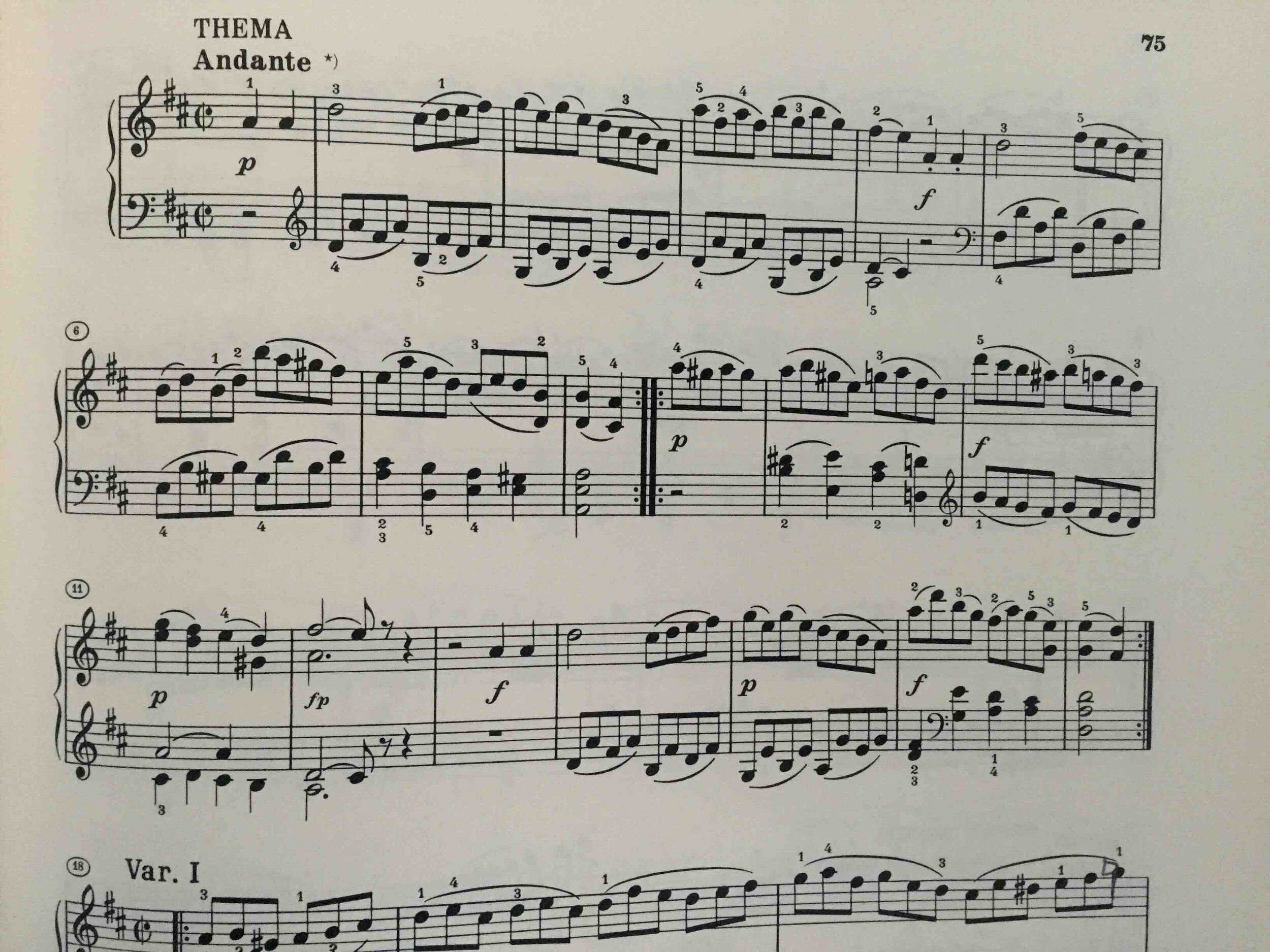

Articulation slurs in Mozart Sonata KV 284, Mvmt 3 from G. Henle Verlag edition.

BILSON: Well, it's hard. I mean, the listeners have to understand what a slur is. A slur is this crescent-shaped sign above a certain number of notes. If it's over two notes, then they called it a sigh. The first note is stressed. The second note is less stressed and is always short. And now it's a little more complicated than that. But not a lot more complicated. It's a little more complicated than that by the simple fact that music also goes up and down.

And, of course, is this piano, is this forte? But the idea that you ever play anything simply smoothly without any inflection… Which many people do. If you accept the idea that they all talk about that music is like speech, then [robotic voice] there-are-no-lang-u-ag-es-like-this

Well, whenever I say this, everybody's laughing. But, listen to the Metropolitan Opera on Saturday sometime you'll hear singers who sing every note the same loudness. And, that's with words.

Not every singer, by the way, but a lot of them do that.

Never, ever play evenly [8:28]

MALTZ: So one thing you say over and over is ‘never, ever play evenly.’ Now, this is radically different to what most musicians are taught. Please explain this.

BILSON: Well, that's what I was just talking about. If music is like speech, then [robotic voice] you-can-not-play-an-y-thing-like-this.

You know, it's very interesting that when you started having robots answering your calls, they said all sounded like that, you know. [robotic voice] The number is 4-5-3-2… and little by little they realized that this does not sound like a person even though there's a person saying it and so they had to introduce [natural-sounding voice] The number is 4-5-3-2… whatever it is, because it's unnatural to speak without inflection. Even if you're just giving a telephone number.

What is tempo rubato? [9:37]

MALTZ: So in the past few minutes we've challenged many accepted modern conventions for interpreting classical music and that's just the beginning of your teachings. In the interest of time, I want to discuss just one more concept and that is tempo rubato.

Louis Armstrong smiling with trumpet. Image via https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Armstrong

BILSON: Tempo rubato has two meanings. One is a later 19th century meaning, which means that you speed up and slow down. But, the 17th and 18th and early 19th century meaning of tempo rubato was quite different. It means that the accompaniment stays steady while the right hand or the violin or the flute or the voice or whatever it is, floats freely above it.

Mozart talks about it – Chopin insisted on it. He insisted on the students practicing, first, the left hand by itself, and then only bringing in the melody later. And, to try to do this, it's very hard. It's very, very hard to do.

It takes a lot of training and, if you want to hear how it's done really superbly, then you go to a recording of people like Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald, who did this spectacularly.

You know, there's a recording of Louis Armstrong playing “Summertime” on his trumpet with an orchestra in the background. He's never near them anywhere. And it's just… it sends you right to heaven.

Cultivating tempo rubato technique [10:57]

MALTZ: You mentioned the difficulty of this technique. So how can a musician go about cultivating this tempo rubato?

BILSON: Well, it's all a question of taste. See, I think that that you have to have taste for anything. But, basically, if anybody starts and says, ‘Look, here's this score. It looks like all these rhythms, are very steady.’ But I know that it's not because [robotic voice] I-do-not-talk-this-way.

So what could it be? And then you start experimenting. Of course, there are rules and these rules – which are talked about by Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach and Leopold Mozart. Chopin wanted to write a book, which he never got around to. But, it's absolutely clear that it's the same rules because the rules in the sense don't really change. You know, high notes are more important than low notes and long notes, more than short notes and all these things. So you start to experiment and you have to have good taste.

Now, I'm thinking of one pianist in particular who has given many lectures on this subject about playing tempo rubato or in the hands, not together and arpeggiating chords and all these wonderful things. And he does all those things. And, in my opinion, it's very tasteless because I just don't think he has good taste.

This is a hard thing to talk about taste. And, in this video, I talk about it and I tried to talk about it in very specific ways.

What got me started on that is that Haydn says to Leopold, Mozart’s father, ‘Your son is the greatest composer known to me because he has number one taste and number two a profound knowledge of composition.’ And it’s true. Taste is first in everything.

You know, it's what makes a great painter greater than an inferior painter: the taste that is developed in the eye, but at some point, you've got to experiment as a painter, or as a musician, and then you have to decide what to keep and what to throw away. It’s not easy.

PRODUCER: Well, that's an interesting idea with painters. We were at a museum in San Diego last week and, in one room, there were two paintings that immediately struck both of us. And, of course, they were from the great masters. We were talking about why did these two affect us? Why did these two capture our eyes? And it’s the taste.

BILSON: Well it's more than taste, it’s insight and stuff like that.

PRODUCER: Of course. But still, there's just that something special.

BILSON: Yeah, it’s true.

Romantic rubato [14:03]

MALTZ: I’ll just ask one more question about this tempo rubato playing. You mentioned that this type of tempo rubato playing is what was in practice for the 17th, 18th, and beginning of the 19th century. Does this mean to say that the other type of rubato, we’ll call it the romantic rubato or where it's mostly just stretching and it's both hands stretching together. Does that mean to say that that didn't exist in classical music?

BILSON: Of course it existed. When you tell a story you want to just take a little bit more time with this part and then you rush over that part cause it's not so important. It's a perfectly natural thing to do. But, you've got to make sure that you take time over the important parts and not unimportant parts. But, that's the tricky part. That's the taste.

MALTZ: And, is that something you said about how music from the 18th century to early 19th century sort of a shift from a more speech-like manner to a more singing-like manner in the later…

BILSON: Something like that, that's right. You know, I try not to… It sounds like Mozart doesn't know how to sing, you see. But it is, true that Mozart's music is operatic and that's speaking and singing together.

Octave leaps [15:23]

MALTZ: You emphasized that the soul of the composition is in the notes and markings from the composer. A great example you give is the opening octave leap in Beethoven's Opus 111. You maintain that how one plays it makes all the difference in the world.

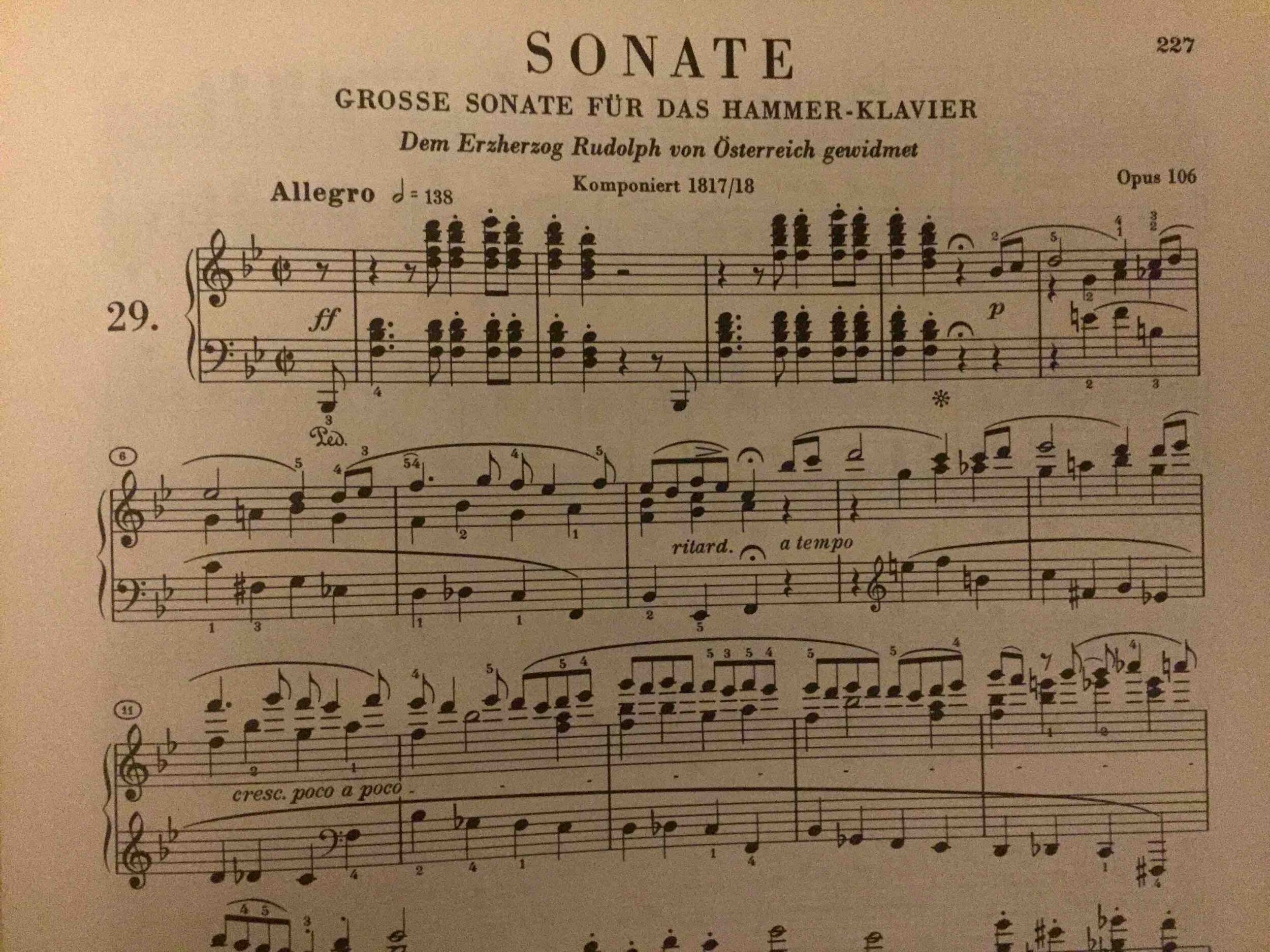

The opening in Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier,” Op. 106 from G. Henle Verlag edition

BILSON: Look, I don't know about soul and things, but composers do write for instruments, including the voice. I mean a tenor like Pavarotti gets a lot of money to sing that one octave above middle C. If I play it on the piano, it’s not worth anything.

When a violin goes up in the high registers or when a bass goes down into the low registers, this is all part of music, you know, and it's very much to do with what the instruments are.

So a better example than opus 111 is the Hammerklavier, which begins with this tremendous leap in the left hand. And there's a very, very good orchestration of that by Felix Weingartner. But the timpani plays a low B flat in the orchestra comes in and the whole excitement of this leap is lost.

But what could he do? He couldn't do anything else.

Competitions [16:38]

MALTZ: In today's world where competitions are king, the concept of going against modern performance practice seems like the opposite of what one might want to do to win. How does a competition entrant reconcile your teachings against the modern international standard?

BILSON: I’ll tell you. First of all, when you have a competition, there are two groups of people who may do well or may do poorly. One of them is the group of people who are playing and the other is the people who are listening. And if the people who are listening are… How should I put it? Less-educated than the people who are playing, they probably won’t advance them.

I have encouraged people to go into competitions, not giving a hoot about whether they win or not.

You know, for one thing… people love competitions. And, the big competitions get big audiences. Years ago, I was in Australia and there was the big, big Sydney competition going on. There was a favorite of the audience named Roger Wright. I don't know what happened to him, an American who was eliminated in the second round.

And, people were angry and said, ‘He's our favorite.’ And they said to Roger Wright ‘How do you feel about this?’ He says, ‘I feel wonderful. I came to this wonderful country, played in this beautiful opera house and met all these wonderful people. I'm very happy.’

And what happened is at the end of the competition, the ABC, Australian Broadcasting Company put out one CD of the winners and another CD of Roger Wright who did just fine.

So I say if you want to go into a competition – excuse my language – screw the judges, just play what you think is convincing. And if you're really good, you'll convince the best judges and there you are.

Suggested Resources to Learn More [18:48]

MALTZ: In addition to watching your videos, where can the audience go to learn more about classical era performance practice?

BILSON: I would recommend Sandra Rosenblum's book, which is now thirty or forty years old, but which is still very good, Performance Practices in Classic Piano Music. It's been translated into several languages, I believe, and she did all her homework. If you want to know what anybody says about the length of a quarter note, she'll tell you that Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach says this on page that and Türk says this on page that and then it's all there. It's a great source for just finding the original things and making up your own mind.

MALTZ: Bilson, thank you for enjoying this Classical Cake with me today.

BILSON: Delicious!

MALTZ: For anyone looking to improve their interpretation of music, I highly recommend Bilson’s videos. You can view them at malcolmbilson.com and on YouTube.